Thursday, February 16, 2017

Wednesday, February 15, 2017

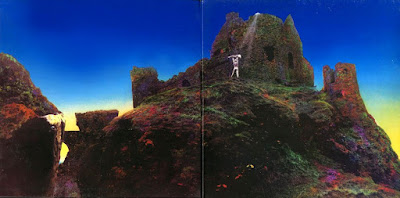

An Album That Changed My Life - Houses of the Holy

The idea for this came from a friend who changed my life almost as much as this album did.

We were supposed to be in church. Well, my friend Mike was anyway.

Somehow, he had arrived at an arrangement with his mother. He would be allowed to go to the late mass, allegedly, with me and Mark. I think it was partly a matter of convenience. With his two sisters, they made a family of five who, as they all got to high school age, probably had a hard time fitting in their little car. So, the rest of them went to the early mass.

I think it was a matter of convenience in another way, too. It was becoming more of a battle to get Mike to worship every week, and, this way, his mother could let herself believe he went to church. And, while out of her sight, he could do what he wanted to do, which was drive around with his friends all afternoon.

That’s how Mark’s car came to be called “The Temple.” On most Sundays, if the surf wasn’t up, I would walk across the street to Mark’s house, and we’d drive around the corner to pick up Mike, ostensibly to go to church. Mark’s car had the best stereo system, so it became our place of worship, a rolling sanctuary where music and marijuana were doled out in strong doses.

We drove for hours, up and down our stretch of the Treasure Coast, from Vero Beach to Jupiter. Between us, we smoked a small forest of marijuana. And we listened to some incredible tunes. But the music selection was dominated by two bands. Pink Floyd. And Led Zeppelin.

Let me tell you a few things about Zeppelin. When they played live, they excelled at escalating their songs to crushing crescendos. A music writer at a Zeppelin show in Boston in 1969 saw concert-goers in the first few rows so invigorated by the band’s performance they began rhythmically slamming their foreheads against the front of the stage. It was from this event, and the subsequent review, that the term “headbangers” was coined.

But Zeppelin doesn’t get enough credit for their ability to unplug from the amps and play without losing their impact. They could be heavy and light. Their name, perhaps more so than any other band name, captures the essence of what they were. Led. Zeppelin.

We explored the Led Zeppelin catalog in order. By then, everyone had heard the first two albums, and witnessed the blues being transformed into crunchy rock before their very ears. Led Zeppelin III was more acoustic and held hints of the Welsh countryside where most of the material was written. This was part of the genius of Led Zeppelin. Each album was distinctly different from the one that preceded it and the one that followed it, but still bore the unmistakable signature of the band.

After that came the fourth album, officially untitled, which combined the band’s different moods and influences with innovative production into something unique and eternal. And, of course, it informed the world that there just might be a Stairway to Heaven.

The next one in line was called Houses of the Holy. This was an album that changed my life.

Each member of the band was at his musical peak. Bassist John Paul Jones had introduced the Mellotron to his repertoire. Robert Plant’s rangy yet throaty voice had never been better. John Bonham’s drumming was powerful to the point of being intimidating. Jimmy Page, in addition to being one of the greatest rock guitar players that’s ever lived, had become a gifted producer.

Page had perfected his technique of recording guitars by placing a microphone right in front of the speaker cabinet, as per the usual method, but also placing a microphone twenty-five feet behind it, and running the combined signal into one channel. The effect of this was that it recorded the sound in the space between the two microphones, and captured the ever-elusive ambience of the room in a simple but remarkable way.

I’ve never heard guitar tones better than those on Houses of the Holy. And they were recorded in 1972.

The album dripped with the raw energy of their earlier work, but it was more refined. It would still test the pain threshold of your ear drums if you wanted it to, but it had a pop sensibility that wasn’t in the first four albums. The subject matter wasn’t confined to the usual sexual angst or medieval lore.

The first track is called “The Song Remains the Same.” Conceptually, it’s a simple expression of unity, the idea that music gives us all common ground. But the song is anything but simple. When I first heard the guitar work, my jaw dropped. It still does.

“Dancing Days” and “Over the Hills and Faraway” are rollicking party songs, the former with a simple but clever guitar riff, the latter with a folky twelve string acoustic opening that segues quickly and powerfully to Page’s layered electric guitars and Plant’s wailing vocals.

“The Crunge” and “D’yer Maker” contain elements of funk and reggae - and humor - that confuse music critics, but, ultimately, display even more of the band’s versatility.

“The Ocean” is a tribute to the fans as they appeared from the band’s point of view on stage – a rocking and rolling sea of people.

“No Quarter” is a dark song that’s dominated in the early portion by Jones’ keyboards. The production style gives it an eerie, almost psychedelic feel. Plant sings of howling dogs of doom and soldiers walking side by side with death. The middle section features an unusual guitar solo by Page, but each member of the band is suitably showcased. When played in concert, it stretched to twelve or fifteen minutes long, and ended in a knee-shaking climax.

Finally, there is “The Rain Song,” a seven and a half minute guitar symphony, with a healthy touch of the Mellotron. Using seasons and weather as an extended metaphor for emotions, Plant’s lyrics tell of the changes that occur in relationships.

I think I knew even then that “The Rain Song” would resonate with me decades into the future.

It was near the end of my senior year in high school. Mike and I were going off to different colleges. Mark was staying behind. Each of us was changing, and we knew it. Our relationship with each other was changing. We knew that too. But we behaved in that peculiar way teenage boys do, unable or unwilling to express complex emotions.

And then comes House of the Holy… with this whole range of feelings I hadn’t expected from a Led Zeppelin album; love, loss, friendship, confusion, sorrow… If the artistic growth of a band can be compared to the course of a human lifetime, like us, this raucus teen was becoming an adult.

I had avoided lengthy relationships with girls. I didn’t do break-ups well. I still don’t. I wanted the trust and comfort level that comes with commitment and time spent together. But I was terrified of being vulnerable, and of what the end might be like. That which I craved most was also that which I feared most.

Some things never change.

My friends and I discussed lyrics that touched us in one way or another, but never talked about why, or how. We recognized the power of music to penetrate pockets of emotion we didn’t want to acknowledge, or didn’t even know we had. But that was as far as we would go. My favorite songs usually expressed the things I felt, but didn’t have the nerve to say.

I will never forget this one Sunday. We were supposed to be in church. Or, at least, my friend Mike was.

But we were in The Temple, driving around, listening to Houses of the Holy. “The Rain Song” came on. It was a beautiful, sunny day. And there was something about that moment that struck us, the three of us.

All the things we were thinking about were there, in one song. Love, loss, friendship, confusion, sorrow. Beginnings… and endings.

Mike piped up from the back seat, and in the long, slow, drawl of someone who was very stoned, said, “Wow. I wish it would rain.”

Just then… I swear to you on a stack of Led Zeppelin albums… I saw a few small splashes on the windshield. Then a few more. Then a steady sprinkle for about thirty seconds. And then it was gone.

“Whoa.”

“Holy shit.”

“Are you kidding me?”

I can’t recall who said what, but I remember hearing those words.

After that, it was a long time before any of us spoke again.

I don’t believe in miracles, so I don’t know what to say about that afternoon, that moment.

Maybe it’s better left unsaid.

When we dropped Mike off a few hours later, his mother was standing in the driveway, smoking a cigarette. As he walked past, she raised a skeptical eyebrow, that gesture of silent interrogation parents do so well. There would have been no use trying to explain that we’d had a spiritual experience far more powerful than any we could have had at St. Patrick’s.

A few weeks later, I was gone. Off to college. I don’t recall any long good-byes. I just… left.

Every time I hear Houses of the Holy, I think of Mike and Mark, and of many other people, too. I think of relationships that didn’t end the way I wanted, or that ended for no reason at all. I think of all the things I left unsaid, and of what I would tell each of those people, if I had the chance.

Because, you see, I can say it now.

But I still can’t say it any better than Robert Plant did...

I’ve felt the coldness of my winter

I never thought it would ever go

I cursed the gloom that fell upon us

But I know that I love you so

******************************************************************

Track Listing –

The Song Remains the Same

The Rain Song

Over the Hills and Faraway

The Crunge

Dancing Days

D’yer Ma’ker

No Quarter

Wednesday, November 16, 2016

Tonight, We Will Know If You Are Warriors

I occasionally like to find memorable moments in college football history and share them. When I first stumbled on this story, I had no idea how absolutely fascinating it would be...

On November 9th, 1912, the Carlisle Indians walked on to Cullum Field at West Point for a much-anticipated game against the Army Cadets. The team from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania had become something of a media sensation. They were in the midst of a three year stretch during which they would compile a record of 33-3-1.

Legendary coach

Legendary coachGlenn "Pop" Warner

had taken advantage of the game's evolving rules, and developed an offense that was as entertaining as it was successful. He employed the forward pass as effectively as any team of the time, and had perfected the "single wing" formation. Now, he was about to reveal a new twist to the Cadets, and the college football world.

Eastern city-dwellers had become fascinated by this team that, like their proud ancestors, incorporated speed, stealth, and deception into their plan of attack. And, of course, the Carlisle squad included Jim Thorpe, only four months removed from winning gold medals for the pentathlon and decathlon in the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm.

Born on a small Sauk and Fox Indian reservation outside of Prague, Oklahoma to a half-Irish and half-Indian father, and a half-French and half-Indian mother, Jim Thorpe was drawn to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School because of its reputation in sports, football in particular.

Born on a small Sauk and Fox Indian reservation outside of Prague, Oklahoma to a half-Irish and half-Indian father, and a half-French and half-Indian mother, Jim Thorpe was drawn to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School because of its reputation in sports, football in particular.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School had been founded in 1879 by Captain Richard Pratt. After serving in the Union army during the Civil War, he had commanded the 10th Cavalry Regiment - the now famous Buffalo Soldiers - and employed many Native Americans as scouts. Recognizing the plight of plains Indians, he became convinced that the best way to end the hostilities with white settlers, and the government, was to force them to abandon their heritage and assimilate into the "majority" culture. "Kill the Indian, save the man," Pratt would say. By 1902, the Federal government had established twenty-six Indian boarding schools designed to provide the knowledge and skills necessary to survive in the white man's world.

By the time Thorpe began playing football, coach Warner had already achieved considerable success at Carlisle, and was responsible for a number of innovations that would fundamentally change the game. He had enhanced the use of the forward pass, and was the first to employ the screen pass. He developed the spiral punt, the use of shoulder and thigh pads, and special helmets. He created the single wing formation and the hidden ball trick.

Thorpe added speed and agility to an already accomplished backfield. On the very first carry of his career, he hesitated, and was tackled for a loss. On the next play, he ran for forty-five yards.

Warner's offense used misdirection like no other coach had. When Carlisle beat perennial powerhouse Harvard for the first time, in 1907, a Boston Herald story on the game said, "Only when a redskin shot out of the hopeless maze... could it be told with any degree of certainty just where the attack was directed."

Warner was the first to encourage his team to use audibles and hand signals, enabling them to communicate more readily while aligning, often with words or gestures unique to Native Americans, and baffling to their opponents. With Thorpe's athletic ability added to the equation, the effect was intimidating.

It was a finely-tuned offensive machine that arrived in West Point in 1912 with a 9-0-1 record, the only blemish being a scoreless tie with Washington and Jefferson College in an uninspired effort that had irritated Warner. But, on this November day, he was certain his Carlisle Indians would find inspiration.

The Army squad also brought an impressive resume to the field. They were in the midst of a four year period in which they would compile a record of 28-5-1. No fewer than nine future generals were on the 1912 team. Among them was a slightly undersized, but powerful athlete named Dwight Eisenhower. They played fierce defense, having surrendered just thirteen points in the four previous games combined.

This game would match Army, and the nation's best defense, against Carlisle, and their high-scoring offense, but the underlying implications were far more significant. If anything symbolized the Native American struggle against intrusion from white settlers and their conflict with the government, it was the Army.

Only twenty-two years before, in 1890, the last major confrontation between the Army and Native Americans occurred when soldiers from the 7th Cavalry surrounded a Lakota camp and massacred 146 men, women and children near Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota.

Although Carlisle began fielding football teams by 1893, fear of open hostility had kept them from scheduling games against Army. Despite being among the top programs of their era, the two teams had met only once prior to 1912, a 6-5 Carlisle victory in West Point in 1905.

When they lined up for the opening kickoff in the 1912 game, it was not only two of the best teams of their day, but old adversaries from bitter battles of the past. In the locker room beforehand, Warner told his players, "Your fathers and your grandfathers fought their fathers. These men playing against you today are soldiers. They are the Long Knives. You are Indians. Tonight, we will know if you are warriors."

Some versions of the story say he also told his players to "remember Wounded Knee." In any event, the intent was clear. He wanted them to know that this was not just one of the biggest games of the year in college football, it was an opportunity for revenge.

As the teams emerged from the locker rooms on a dreary day, Dwight Eisenhower prowled the Army sideline glaring at Jim Thorpe. Eisenhower had become the leader on a team of leaders, mostly through sheer determination. In those days, players stayed on the field for offense and defense, and, although he was a solid halfback, it was as a linebacker that Eisenhower hoped to, literally, make his biggest impact that day.

Months before, when he had first learned that Carlisle would be paying a visit to West Point, Eisenhower had begun dreaming about tackling Thorpe in a way that would leave a lasting impression. If he could intimidate him, that would be great. If he could knock him out of the game, that would be even better.

On at least two occasions in the first half, Eisenhower hit Thorpe as hard as he could, once forcing a fumble, and once combining with one of his teammates in a collision that left all three players dazed on the ground.

At first, Army used their superior strength and size to overpower the Indians, taking a 6-0 lead after scoring a touchdown and missing the extra point. The Army players were, on average, four inches taller and twenty-five pounds heavier than the Indians. But the Carlisle offense was a blur of motion and trickery, and the Cadets were soon running all over the field trying to make sense of it, and trying to stop it.

A New York Tribune correspondent wrote, "The shifting, puzzling, and dazzling attack of the Carlisle Indians had the Cadets bordering on a panic. None of the Army men seemed to know just where the ball was."

The standard formation of the day had two halfbacks and a fullback in the backfield, behind the quarterback. It was a power formation that could concentrate blockers in one area for maximum effect. But Carlisle had begun using a single wing formation developed by Warner. One of the halfbacks would line up just behind the line of scrimmage on the shoulder of the tackle. Aligning that way would put him outside the defensive end, giving him a good angle to throw a block, but also giving him room to escape from the backfield to catch a pass. And it gave him time to build a head of steam if he were to run around the opposite end behind the line of scrimmage on a reverse. Basically, it was the earliest incarnation of the spread offense.

Now Warner decided to unleash the latest variation on his offense. The Indians had worked on it all summer, but had chosen not to show it until now. They wanted "the soldiers" to be its first victim.

They broke the huddle and shuffled into a standard alignment, but, on a signal from quarterback Gus Welch, shifted into a "double wing." Alex Arcasa, at right halfback, shifted to a spot outside the right tackle. Thorpe, at left halfback, moved outside the left tackle. The Indians then embarked on a series of reverses, double reverses and fleaflickers. No one had ever seen anything like it.

A New York Times story on the game reported, "Thorpe tore off runs of ten yards or more so often that they became common." He would rush for nearly 200 yards on twenty-four carries. He scored twenty-two of Carlisle's twenty-seven points.

Eisenhower would never get the knockout blow he hoped for. Early in the second half, he lunged at a sprinting Thorpe, but, in a remarkable display of agility, Thorpe stopped in his tracks and watched as Eisenhower crashed into his own teammate. Although he didn't know it at the time, Eisenhower had ruined his knee trying to make the tackle, and effectively ended his football career. Unable to continue, he spent the rest of the game in the locker room, fuming.

They had kept the game close, trailing 7-6 at halftime, but the exhausted Cadets were unable to move the ball in the second half. They couldn't even manage a first down as Carlisle pulled away to win 27-6.

After the game, reporters asked Army team captain Leland Devore about Thorpe's performance. "He is super-human," he said. "That is all. There is no stopping him."

The Indians would finish the season at 12-1-1. A 34-26 loss at Pennsylvania cost them a national championship.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was closed in 1918, and the property was used as a hospital for wounded soldiers returning from World War I. The Carlisle Barracks are now the home of the Army War College.

Jim Thorpe would go on to play professional football, baseball and basketball, but the man often considered to be the greatest American athlete of the twentieth century struggled later in life, particularly during the Great Depression. He was stripped of his Olympic medals in a controversy over his amateur status (they were reinstated in 1982). Failed marriages and trouble with alcohol plagued him.

When he died in 1953, he was living in a trailer home in Lomita, California. His family received a telegram from the White House, condolences from president Dwight Eisenhower.

Tuesday, October 4, 2016

Thursday, August 25, 2016

Monday, May 2, 2016

Reading "My Highness" - Storytelling 2016

This is moi, reading "My Highness" at the Storytelling 2016 - Emotionally Powerful Storytelling event. The Sleeping Moon is a lovely venue.

Thursday, April 14, 2016

What the Hell?

Note: I wrote this to read on stage at the Short Attention Span Storytelling Hour - an event organized by the Writers of Central Florida or Thereabouts. I started writing about drugs, and, somehow, it turned into my life story. This is the third installment of my unplanned memoir.

What the hell?

When I booked my first live music event, and joined the world of rock concert promoters, I had no idea that would be among my most useful and frequently-uttered phrases for the next several years.

That simple sentence could stand by itself... What the hell? Or, when someone did something stupid, irresponsible or downright dangerous, I could make it more expressive by adding different endings to it, like... are you doing?... were you thinking?... or... is wrong with you?

For special occasions, I would use the more definitive version... What in the fucking hell? To which I could also add the previously mentioned endings.

I had always been a music lover and an avid concert-goer, but I never intended to get into concert promotion. After graduating from college in Gainesville, I had done several media and advertising-related jobs, and was kind of enjoying myself working as s sports writer.

By then, I was married, and feeling pressure to find a stable job with a solid income. I had set my sights on the best advertising sales position in the market - one of the University of Florida's commercial radio stations, ROCK 104.

Two things happened. A friend of mine who worked at ROCK 104 resigned. That was my opening. Then, shortly after I was hired, an important local advertiser called. His name was Andy Shaara. He owned the world famous Purple Porpoise, a large party complex right across from campus. He had a music venue called the Blowhole, and he wanted to work with the radio station to do more live events. Partly because I knew a few things about music, and partly because I knew Andy, the assignment fell to me.

And it changed my life.

I was introduced to Hound Dog, the house sound guy in the Blowhole. Andy urged me to hire him for my shows. Hound Dog was an old Southern rock veteran with a scraggly exterior and a heart of gold.

He had simple and direct ways of making a point, and he taught me many of the things I would need to know... about the equipment, the lingo, and the nature of the people we'd be working with.

Once, he asked me, "Do you know how you can tell when the drum riser is level?"

I had no idea.

He said, "If the drummer's drooling out of both sides of his mouth."

He became an important part of our operation.

ROCK 104 couldn't really promote their own shows. The university affiliation made the paperwork process cumbersome. So it dawned on me that I could start my own company - Rock Solid Promotions - and promote shows myself. The radio station would provide cheap or free advertising in return for being able to attach their name to the show, and give away a certain amount of tickets and perks to listeners, but I would take the financial risk.

And there is some serious risk in concert promotion.

Established, national bands get a guaranteed payout, whether you sell two tickets or two thousand. I had to choose bands that people would pay to see, negotiate a reasonable guarantee, provide the necessary equipment and staff, and do a good enough job getting the word out so people would actually buy tickets and show up. And that doesn't even factor in the liability for bodily injury...

Despite the risk, it was a cool opportunity. This was my chance to treat every band with respect, provide a professional environment for them to showcase their talents, and, hopefully, have a few bucks left over for my efforts.

But I soon learned that every show was like walking through a minefield. The bigger the show, the bigger the mines. At any given moment, a thousand things could go wrong.

There were lights, smoke generators, equipment trusses and pieces of staging that could crumble without warning. And various electronic items that would simply cease to work for no discernible reason. Microphones broke, cables short-circuited, speakers blew, and buzzing mysteriously appeared in the PA.

The first time we had a national band, they drove the sound system so hard the amplifiers overheated, and the PA cut out in the middle of their set. Twice. I spent most of the show in desperation off to the side of the stage holding a fan over the amps in an effort to keep them functioning. The next day, we got new ones.

We survived that, and dozens of other incidents. We did many smaller shows with local and regional bands while we learned to work together and anticipate problems. We developed a reputation for running a tight ship. The rock music business is a relatively small fraternity, and word got out. Bands liked playing our shows. So the shows got bigger. And better. I stopped calling booking agents. They started calling me.

If you're a fan of nu-rock, you'll recognize some of the names... Breaking Benjamin, Hoobastank, Nickelback, Days of the New, Fuel, Filter, Chevelle, Three Doors Down, Saliva, Sevendust...

But it's impossible to dive deeply into that world without suffering from it somehow. Hunter Thompson is widely quoted as saying, "The music business is a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs. There's also a negative side."

I was sure I would never become one of the people I despised. I would be honest. I would stay committed to the music, and not the money.

It wasn't musicians that sucked the life out of me, at least not at first. It was the handlers, managers, agents and lawyers. But they got sour from dealing with shady promoters and venues. Everyone trying to make a quick buck off everyone else.

Normally, band performance contracts stipulate a certain percentage split in the profits after a promoter reaches the break-even point on a show. I didn't like doing math at the end of the night, so I built in a flat bonus. Sell "x" number of tickets, get an extra five hundred or thousand bucks, or whatever it was.

One night, after a successful show, the tour manager for the headlining band approached me, and I could tell from his body language he was ready for a confrontation. He asked if they were getting their bonus. He must have assumed I would pad my expenses, misreport ticket sales or come up with some other bullshit excuse for not paying.

But I said, "Absolutely! It was a great night, great crowd, and your guys were awesome. Let me finish cashing out the openers, and I'll bring you your money and we'll have a beer."

And he almost fell down. His demeanor changed immediately. But that's how it usually was... Everyone expected the worst, right up until the moment that it didn't happen.

Tour managers were part of the problem. It's their job to advocate for their band, make sure they're fed and lubed, and that they look and sound as good as they can. Many of them thought that meant complaining about everything the minute they showed up for load-in... lights, amps, PA, monitors, mixing console, and even the brand of bottled water in the dressing room...

What the hell?

Hound Dog helped to keep people in their place. I recall a soundcheck for a band of young hotshots when the singer kept getting feedback in his monitors. I was with Hound Dog behind the front of house mixing console, watching him calmly drag from a cigarette and sip from a bottle of Budweiser while the singer continued to make a common mistake. He just wanted to be loud, so he was gripping the mic with both hands and cramming it into his face to get it as close to his mouth as he could.

After starting and stopping several times, the singer was frustrated.

Hound Dog leaned forward to flip the talk-back switch, "Want my advice?"

The kid shrugged and then nodded.

"Stop holding the microphone like you're sucking a cock."

Good old Hound Dog...

I was never a celebrity worshipper, and that worked in my favor when dealing with some pretty well-known people. I treated them like human beings. They weren't used to that. Sometimes, we'd just sit around and chat after load-in and soundcheck was done, before the crowd arrived.

One band was ecstatic when I drove them to Starbucks for coffee. They were grateful just to be someplace other than the back of their tour bus or the bowels of a venue that smelled like stale beer and dried vomit.

Usually, the guys would relax and open up a bit. Carl Bell from Fuel told me his favorite musician joke.

"What does a stripper do with her asshole before she goes to work? Drops him off at band practice."

Heavy drinking was part of the culture. We worked while we were standing around drinking, the same way bankers cut deals on the golf course, I guess. We discussed ideas, and hammered out details. That's how business got done.

I don't think my wife ever really believed that. Somewhere during this period, she became... my ex-wife.

Eventually, things got ridiculous.

After I decided to get into artist management, several record labels were interested in one of our bands, so their A&R people all wanted to talk to me.

And there was one festival where every conversation started with someone grabbing my arm, pulling me away, saying, "Let me buy you a drink."

In my backstage wanderings, I vaguely recall meeting Kyle Cook from Matchbox 20, Brent Smith from Shinedown, and studio guy Russ T Cobb, who produced Avril Lavigne's first record, among other things. But, by this time, I was having a hard time speaking. I wasn't out of control. But it wasn't good.

And then there was the time I got in a Jagermeister drinking contest with guys from Saliva and Sevendust. Frequently, when I tell people that, they want to know who won. I can assure you... nobody wins a Jagermeister drinking contest.

Because of my advertising background, I involved sponsors in all my shows, usually beers and liquors. I hung out with a guy who was a tour liaison for Jagermeister. As far as I could tell, his key function was delivering bottles of Jager to the tour buses after the show.

We went on one bus, and the band guys were sitting around the table. On top of the table was a naked woman on her hands and knees. And the guys were, rather casually, taking turns using drumsticks to penetrate certain entrances to her body. Although I think you could argue that one of them was more of an exit.

Everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves, but I was pretty uncomfortable. They invited us to stay, but, fortunately, we had more Jager to deliver.

When we stepped off the bus, all I could say was, "Dude, what the hell?"

My friend just laughed, and said, "It's rock and roll, Brian. You should know that by now."

Rock and roll certainly has a dark side, and, for me, it kind of had a cumulative effect.

I watched the beginning of one show from the wings of the stage, and wondered why a roadie was standing behind the speaker stack with a garbage bag. And then, about two songs in, the lead singer walked back behind the stack and puked in the bag. Someone told me, when you snort heroin, vomiting is a common side effect. This was routine.

Heroin was one drug I never tried. I was afraid I would like it.

Once, before a show, I watched Travis Meeks from Days of the New wander off into the crowd to beg for tranquilizers.

"Dude, got any tranquilizers? No? Hi sweetheart, got any tranquilizers? Hey man, got any tranquilizers?"

I guess he'd run out.

I spent an afternoon driving around with Richie Patrick from Filter. They'd had the previous day off, and he spent it alone in his hotel room. I didn't see him consume anything, but, when I picked him up, he was not well. Mostly, he just seemed... sad. And lonely.

A week later he checked into rehab.

I mention those two by name because their troubles are well-documented.

For years, I'd been enamored with music, and fascinated by the people who made it, and I had finally broken into this world that seemed so glamorous and exciting, and it really... wasn't. It made you realize your childhood fantasies were... just that. It was like finding out Peter Pan died of old age.

It was bad enough watching people damage themselves in the name of music, but, as I got further up the ladder, it changed me.

I was co-managing a band with a good friend, and record labels loved them. They were kind of an updated version of Alice in Chains with a touch of Linkin Park. They were going to be huge. We had a Friday dinner with our lawyer and the VP for A&R from the label we chose, who happened to be a good friend. It was the best possible scenario for a baby band. And a half-million dollar advance upon signing, which meant a fifty thousand dollar payday for me.

And the band chose that weekend to tell me the drummer and the guitar playing weren't getting along.

What in the fucking hell?

The guitar player wrote all the melodies. The drummer just drummed. So it was very clear in my mind. The drummer's gotta go, right? Shitcan the old one, bring in a new one, and we're good.

I went to Europe for three weeks, determined not to think about it, and anxious to quell the urge to murder the little bastard drummer.

When I got back, my business partner had a whole string of messages from the band, talking about their history and their commitment to each other, and all this crap. We wouldn't have to fire one of the guys. They were breaking up.

And I realized, I had given no thought to the human side of it. I hadn't cared about witnessing the painful unraveling of long friendships. It didn't dawn on me that the stress they felt must have been as great as the stress on us. Probably more...

I wanted to manage a famous band. I wanted... the paycheck. And I realized my passion for music and musicians had been replaced by a lust for money and prestige.

I had become... one of the people I despised.

As I thought about it, I decided, there and then, I was done.

We had a little independent A&R operation during the year or so that it took me to disengage, and for the phone calls and the e-mails to stop.

In retrospect, I liked the responsibility, calling the shots, and being the one everyone looked to when things started going wrong. When a show was really cranking, we would look at each other across the room... me and Hound Dog... and my production manager Matt Adams... and there was a strong sense of satisfaction.

Hound Dog liked nothing more than making bands sound good and making people happy with music.

Cancer killed him last year.

I left with lots of good memories, and many other moments I've probably forgotten. Over the years, I've turned down every offer to get back into it. It's a profession that doesn't reward ethical behavior, so it's not for me.

And I don't miss it.

If I may use the words of Grace Slick when describing her career, "It was kind of like high school. It was fun, but I wouldn't want to do it again."

Actually, there is one thing I miss... ten years of never having to pay to go to a concert. Have you seen the ticket prices these days?

What the hell?

What the hell?

When I booked my first live music event, and joined the world of rock concert promoters, I had no idea that would be among my most useful and frequently-uttered phrases for the next several years.

That simple sentence could stand by itself... What the hell? Or, when someone did something stupid, irresponsible or downright dangerous, I could make it more expressive by adding different endings to it, like... are you doing?... were you thinking?... or... is wrong with you?

For special occasions, I would use the more definitive version... What in the fucking hell? To which I could also add the previously mentioned endings.

I had always been a music lover and an avid concert-goer, but I never intended to get into concert promotion. After graduating from college in Gainesville, I had done several media and advertising-related jobs, and was kind of enjoying myself working as s sports writer.

By then, I was married, and feeling pressure to find a stable job with a solid income. I had set my sights on the best advertising sales position in the market - one of the University of Florida's commercial radio stations, ROCK 104.

Two things happened. A friend of mine who worked at ROCK 104 resigned. That was my opening. Then, shortly after I was hired, an important local advertiser called. His name was Andy Shaara. He owned the world famous Purple Porpoise, a large party complex right across from campus. He had a music venue called the Blowhole, and he wanted to work with the radio station to do more live events. Partly because I knew a few things about music, and partly because I knew Andy, the assignment fell to me.

And it changed my life.

I was introduced to Hound Dog, the house sound guy in the Blowhole. Andy urged me to hire him for my shows. Hound Dog was an old Southern rock veteran with a scraggly exterior and a heart of gold.

He had simple and direct ways of making a point, and he taught me many of the things I would need to know... about the equipment, the lingo, and the nature of the people we'd be working with.

Once, he asked me, "Do you know how you can tell when the drum riser is level?"

I had no idea.

He said, "If the drummer's drooling out of both sides of his mouth."

He became an important part of our operation.

|

| Hound Dog being Hound Dog. |

ROCK 104 couldn't really promote their own shows. The university affiliation made the paperwork process cumbersome. So it dawned on me that I could start my own company - Rock Solid Promotions - and promote shows myself. The radio station would provide cheap or free advertising in return for being able to attach their name to the show, and give away a certain amount of tickets and perks to listeners, but I would take the financial risk.

And there is some serious risk in concert promotion.

Established, national bands get a guaranteed payout, whether you sell two tickets or two thousand. I had to choose bands that people would pay to see, negotiate a reasonable guarantee, provide the necessary equipment and staff, and do a good enough job getting the word out so people would actually buy tickets and show up. And that doesn't even factor in the liability for bodily injury...

Despite the risk, it was a cool opportunity. This was my chance to treat every band with respect, provide a professional environment for them to showcase their talents, and, hopefully, have a few bucks left over for my efforts.

But I soon learned that every show was like walking through a minefield. The bigger the show, the bigger the mines. At any given moment, a thousand things could go wrong.

There were lights, smoke generators, equipment trusses and pieces of staging that could crumble without warning. And various electronic items that would simply cease to work for no discernible reason. Microphones broke, cables short-circuited, speakers blew, and buzzing mysteriously appeared in the PA.

The first time we had a national band, they drove the sound system so hard the amplifiers overheated, and the PA cut out in the middle of their set. Twice. I spent most of the show in desperation off to the side of the stage holding a fan over the amps in an effort to keep them functioning. The next day, we got new ones.

We survived that, and dozens of other incidents. We did many smaller shows with local and regional bands while we learned to work together and anticipate problems. We developed a reputation for running a tight ship. The rock music business is a relatively small fraternity, and word got out. Bands liked playing our shows. So the shows got bigger. And better. I stopped calling booking agents. They started calling me.

|

| Me. Monster limo. |

If you're a fan of nu-rock, you'll recognize some of the names... Breaking Benjamin, Hoobastank, Nickelback, Days of the New, Fuel, Filter, Chevelle, Three Doors Down, Saliva, Sevendust...

But it's impossible to dive deeply into that world without suffering from it somehow. Hunter Thompson is widely quoted as saying, "The music business is a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs. There's also a negative side."

I was sure I would never become one of the people I despised. I would be honest. I would stay committed to the music, and not the money.

It wasn't musicians that sucked the life out of me, at least not at first. It was the handlers, managers, agents and lawyers. But they got sour from dealing with shady promoters and venues. Everyone trying to make a quick buck off everyone else.

Normally, band performance contracts stipulate a certain percentage split in the profits after a promoter reaches the break-even point on a show. I didn't like doing math at the end of the night, so I built in a flat bonus. Sell "x" number of tickets, get an extra five hundred or thousand bucks, or whatever it was.

One night, after a successful show, the tour manager for the headlining band approached me, and I could tell from his body language he was ready for a confrontation. He asked if they were getting their bonus. He must have assumed I would pad my expenses, misreport ticket sales or come up with some other bullshit excuse for not paying.

But I said, "Absolutely! It was a great night, great crowd, and your guys were awesome. Let me finish cashing out the openers, and I'll bring you your money and we'll have a beer."

And he almost fell down. His demeanor changed immediately. But that's how it usually was... Everyone expected the worst, right up until the moment that it didn't happen.

Tour managers were part of the problem. It's their job to advocate for their band, make sure they're fed and lubed, and that they look and sound as good as they can. Many of them thought that meant complaining about everything the minute they showed up for load-in... lights, amps, PA, monitors, mixing console, and even the brand of bottled water in the dressing room...

What the hell?

Hound Dog helped to keep people in their place. I recall a soundcheck for a band of young hotshots when the singer kept getting feedback in his monitors. I was with Hound Dog behind the front of house mixing console, watching him calmly drag from a cigarette and sip from a bottle of Budweiser while the singer continued to make a common mistake. He just wanted to be loud, so he was gripping the mic with both hands and cramming it into his face to get it as close to his mouth as he could.

After starting and stopping several times, the singer was frustrated.

Hound Dog leaned forward to flip the talk-back switch, "Want my advice?"

The kid shrugged and then nodded.

"Stop holding the microphone like you're sucking a cock."

Good old Hound Dog...

I was never a celebrity worshipper, and that worked in my favor when dealing with some pretty well-known people. I treated them like human beings. They weren't used to that. Sometimes, we'd just sit around and chat after load-in and soundcheck was done, before the crowd arrived.

One band was ecstatic when I drove them to Starbucks for coffee. They were grateful just to be someplace other than the back of their tour bus or the bowels of a venue that smelled like stale beer and dried vomit.

Usually, the guys would relax and open up a bit. Carl Bell from Fuel told me his favorite musician joke.

"What does a stripper do with her asshole before she goes to work? Drops him off at band practice."

Heavy drinking was part of the culture. We worked while we were standing around drinking, the same way bankers cut deals on the golf course, I guess. We discussed ideas, and hammered out details. That's how business got done.

I don't think my wife ever really believed that. Somewhere during this period, she became... my ex-wife.

|

| Ric Trapp (L) in control. I'm (R) supervising. Or staring off into space, apparently. |

After I decided to get into artist management, several record labels were interested in one of our bands, so their A&R people all wanted to talk to me.

And there was one festival where every conversation started with someone grabbing my arm, pulling me away, saying, "Let me buy you a drink."

In my backstage wanderings, I vaguely recall meeting Kyle Cook from Matchbox 20, Brent Smith from Shinedown, and studio guy Russ T Cobb, who produced Avril Lavigne's first record, among other things. But, by this time, I was having a hard time speaking. I wasn't out of control. But it wasn't good.

And then there was the time I got in a Jagermeister drinking contest with guys from Saliva and Sevendust. Frequently, when I tell people that, they want to know who won. I can assure you... nobody wins a Jagermeister drinking contest.

Because of my advertising background, I involved sponsors in all my shows, usually beers and liquors. I hung out with a guy who was a tour liaison for Jagermeister. As far as I could tell, his key function was delivering bottles of Jager to the tour buses after the show.

We went on one bus, and the band guys were sitting around the table. On top of the table was a naked woman on her hands and knees. And the guys were, rather casually, taking turns using drumsticks to penetrate certain entrances to her body. Although I think you could argue that one of them was more of an exit.

Everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves, but I was pretty uncomfortable. They invited us to stay, but, fortunately, we had more Jager to deliver.

When we stepped off the bus, all I could say was, "Dude, what the hell?"

My friend just laughed, and said, "It's rock and roll, Brian. You should know that by now."

|

| It wasn't ALL bad. |

Rock and roll certainly has a dark side, and, for me, it kind of had a cumulative effect.

I watched the beginning of one show from the wings of the stage, and wondered why a roadie was standing behind the speaker stack with a garbage bag. And then, about two songs in, the lead singer walked back behind the stack and puked in the bag. Someone told me, when you snort heroin, vomiting is a common side effect. This was routine.

Heroin was one drug I never tried. I was afraid I would like it.

Once, before a show, I watched Travis Meeks from Days of the New wander off into the crowd to beg for tranquilizers.

"Dude, got any tranquilizers? No? Hi sweetheart, got any tranquilizers? Hey man, got any tranquilizers?"

I guess he'd run out.

I spent an afternoon driving around with Richie Patrick from Filter. They'd had the previous day off, and he spent it alone in his hotel room. I didn't see him consume anything, but, when I picked him up, he was not well. Mostly, he just seemed... sad. And lonely.

A week later he checked into rehab.

I mention those two by name because their troubles are well-documented.

|

| ROCK 104 crew with Sevendust. I'm in the yellow hat. |

For years, I'd been enamored with music, and fascinated by the people who made it, and I had finally broken into this world that seemed so glamorous and exciting, and it really... wasn't. It made you realize your childhood fantasies were... just that. It was like finding out Peter Pan died of old age.

It was bad enough watching people damage themselves in the name of music, but, as I got further up the ladder, it changed me.

I was co-managing a band with a good friend, and record labels loved them. They were kind of an updated version of Alice in Chains with a touch of Linkin Park. They were going to be huge. We had a Friday dinner with our lawyer and the VP for A&R from the label we chose, who happened to be a good friend. It was the best possible scenario for a baby band. And a half-million dollar advance upon signing, which meant a fifty thousand dollar payday for me.

And the band chose that weekend to tell me the drummer and the guitar playing weren't getting along.

What in the fucking hell?

The guitar player wrote all the melodies. The drummer just drummed. So it was very clear in my mind. The drummer's gotta go, right? Shitcan the old one, bring in a new one, and we're good.

I went to Europe for three weeks, determined not to think about it, and anxious to quell the urge to murder the little bastard drummer.

When I got back, my business partner had a whole string of messages from the band, talking about their history and their commitment to each other, and all this crap. We wouldn't have to fire one of the guys. They were breaking up.

And I realized, I had given no thought to the human side of it. I hadn't cared about witnessing the painful unraveling of long friendships. It didn't dawn on me that the stress they felt must have been as great as the stress on us. Probably more...

I wanted to manage a famous band. I wanted... the paycheck. And I realized my passion for music and musicians had been replaced by a lust for money and prestige.

I had become... one of the people I despised.

As I thought about it, I decided, there and then, I was done.

We had a little independent A&R operation during the year or so that it took me to disengage, and for the phone calls and the e-mails to stop.

|

| Matt Adams (L) kicking back in a limo. |

In retrospect, I liked the responsibility, calling the shots, and being the one everyone looked to when things started going wrong. When a show was really cranking, we would look at each other across the room... me and Hound Dog... and my production manager Matt Adams... and there was a strong sense of satisfaction.

Hound Dog liked nothing more than making bands sound good and making people happy with music.

Cancer killed him last year.

I left with lots of good memories, and many other moments I've probably forgotten. Over the years, I've turned down every offer to get back into it. It's a profession that doesn't reward ethical behavior, so it's not for me.

And I don't miss it.

If I may use the words of Grace Slick when describing her career, "It was kind of like high school. It was fun, but I wouldn't want to do it again."

Actually, there is one thing I miss... ten years of never having to pay to go to a concert. Have you seen the ticket prices these days?

What the hell?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)